QueryTracker, Incomplete Datasets, and Mental Health

Image depicting QueryTracker’s landing page.

It’s one of the first pieces of advice I was given when I started querying my first book back in 2020. “Check out QueryTracker. It’s so useful.”

And it is!

This isn’t a takedown of QueryTracker. I have used it in every querying journey I’ve made and frankly would have been lost without it. It was (and remains) a fantastic one-stop-shop for finding a whole list of agents who represent your genre and age group to begin compiling your query list.

But as a Data Analyst, I also think that QueryTracker is a double edged sword, and as a Data Analyst who focuses in HR (where some pieces of data cannot legally be shared without explicit permission), I know the tricky experience of dealing with datasets that are fundamentally incomplete in the face of stakeholders (in this case, yourself) who want them to be complete.

Because that’s the big issue:

QueryTracker is a fundamentally incomplete dataset.

So let’s talk about that—how to guard yourself from making some “data-driven” missteps, and also better understand how data can be, should be, and shouldn’t be used.

The Dataset

QueryTracker is a repository of self-reported querying data. It only has the data of those who choose to use it and also remember to update it. This is important and I think frequently is what gets forgotten quickly. On the one hand, it’s very easy to go “yeah, duh, that’s what QueryTracker is. You know this, I know this. You’re not saying anything new.” On the other hand, when you’re scrounging through the raw data trying to understand whether or not you’re in a “maybe” pile, whether or not you will get an answer this week, the percentage of full requests that turn into an offer from any individual agent, if you’re looking at the manuscript request timeline on an agent to guesstimate how far away from your own they might be, this crucial framing and understanding falls to the wayside very quickly.

The data is only as accurate as what is provided, and the data is also only the tip of the iceberg in terms of what agents are working on at any given point. I’ve seen agents talk on Twitter about getting a thousand queries the week they open; when I look at their QueryTracker pages, they’re definitely knee deep in fresh queries, but there aren’t nearly a thousand queries present in their raw self-reported data. Maybe those agents are exaggerating; maybe they’re not. But I’m more inclined to believe that no matter what, the numbers will never align.

QueryTracker at some point between querying my last book and querying my most recent book set up an automatic dataflow you can opt into between an agent’s QueryManager account and QueryTracker, since the two platforms are developed by the same organization. This is great; I am delighted by it because everyone’s least favorite activity is getting a rejection and then having to go in and log it on QueryTracker. However even this flow-over has its issues.

Even if it exists, not everyone uses it because not all querying authors use QueryTracker

I’ve noticed there are some data discrepancies that crop up due to inconsistencies in this flow-over. I’ve had to go in and correct something QueryTracker thinks is a Full Request because it was actually a Partial Request. (How many people actually go in and make that correction, though? Do people assume that it’s flowing over properly?) That discrepancy will mess with the overarching dataset. The moment I made that change, it took me off the “automatic flow-over” path as well, which meant I was back to the manual maintenance of this individual query.

When looking at reports, it’s easy to forget just how messy the underlying data is. Reports and even raw datasets are just showing you a portion of what’s out there. They may be a very “accurate” reduction of what might be a wider statistical truth, or they might lead you off-base.

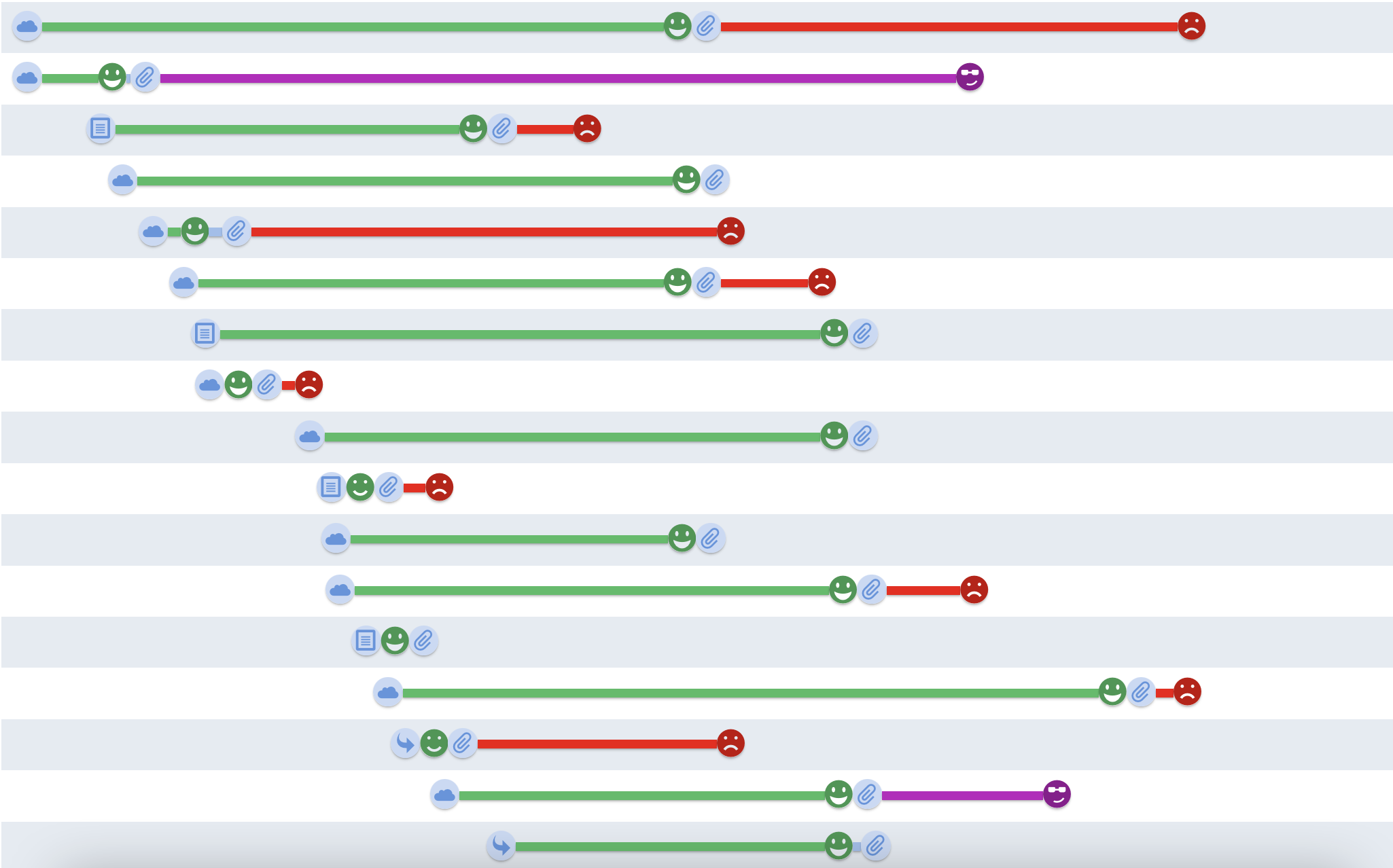

On top of that, a lot of reports don’t show what happens with partial manuscript requests and R&Rs when they happen. The timeline view for the agent I signed with does not reflect the offer status I moved the query to because their first request was a partial request that turned into a full request that turned into an offer. (Believe me, I wanted to see that line in the timeline view turn purple; I even submitted a ticket to be told that this was not a bug.) But for everyone who is looking at that timeline view, they’re going to see one lone little sci-fi partial manuscript request that looks like it’s still pending, even ghosted, when it turned into an accepted offer.

An incomplete dataset will lead to narrative gaps. Sometimes you can guess what an agent’s reviewing pattern is, but not always. Sometimes you can predict when you’ll get a query response, but not always. You can see how many manuscripts the agent is currently reviewing but… can you? Especially when you factor in that that agent might also be reviewing client manuscripts, performing other agent duties, or maybe working multiple jobs as so many agents do?

The incomplete data means you have an incomplete picture of a section of an agent’s job. And that is where the brain will do what the brain always does: it will provide the narrative.

Filling in the Gaps

There are ways to fill in the gaps, of course. The comments section on any agent’s profile, for example, might provide some anecdotal data. But it can be challenging to tie these anecdotal items back to the item of data they’re talking about and… not everyone puts things in the comments. (I typically didn’t. Too lazy/cbf’ed.) Which means that the comments section is an incomplete supplement to the incomplete dataset.

Sometimes, there are things you can learn with time, or someone pointing them out to you. I used to lose my mind over manuscripts that got requested after mine and which were either offered on/rejected within a week. It took me until the second book that I was querying to realize these were likely the “I got an offer of representation and you now have a two week clock to give me an offer” nudges. I used to think they were the agent finding their dream manuscript in their query pile and I was never the dream manuscript and I would just melt about it. Any one of these might well have been that case: an agent getting so excited over a query that they Drop Everything To Read. But all of them? Absolutely not.

Image reflecting QueryTracker’s Timeline Review, filtered to reflect requested pages and manuscripts. The agent does not necessarily read submissions in order of date requested/received.

Especially for agents with long careers, their summary reports (especially the ones indicating response times) will give you the average for their entire time agenting; you have to pay for the ones that filter down to the last 12 months or less, which means that if you’re using the free version of QueryTracker, you might be presented with summaries that aren’t remotely indicative of the agent’s current patterns. And especially since many agents who have been agenting for years have talked about drastic shifts in timelines since 2020, looking at the complete dataset really might skew your understanding of current practice.

Screenshots taken from the same agent depicting QueryTracker’s “Query Response Time” summary report. The first has no filter; the second has QueryTracker’s paid filter to reflect the past 12 months.

And then, of course, there’s the dreaded “maybe” pile. We’ve all been there, looking at the raw data and seeing that there’s no data next to your highlighted yellow query line, but there are a bunch of rejections on either side. Are you a “maybe”? Did a glitch happen/did you hit the spam filter and the agent never received your materials? Or does the agent maybe look at queries by genre: they know they’re in a Thriller mood, so they’re looking at their Thriller queries but you’re a Fantasy, so they’re holding off? Sometimes agents will express what they’re reading through on Twitter, but what if you avoid Twitter like the plague and miss that update?

Image reflecting QueryTracker’s Data Explorer tool, which allows you to view the raw self-reported data attached to any individual agent. This agent receives queries via email, and seems to go through their queries in order, but also leaves some for later; the data subset presented also shows both a full request and a rejection that appear out of this chronological query review.

Anxiety is a bear while querying. Trauma responses are too. Perhaps at a later date, I’ll go down the rabbit hole of how you can protect your brain more broadly during this whole process because it is vital, but a thing that a brain is very good at doing is convincing you it has reached the correct logical conclusion. It will confirmation bias its way through an incomplete dataset, incomplete reports, and incomplete analytical functioning and insist that it is correct. And you will believe it because, well, it’s your brain and you’re a smart person. (And you are—this isn’t to say you’re not! It’s simply to say that our brains are far more adept at tricking us than we would like to admit.)

And ultimately, clinging to this data and treating it as a be-all-and-end-all is an attempt to give yourself some semblance of control over a process—and an industry—where you will likely never have nearly enough control.

So… what now?

I have been at my happiest querying by looking at QueryTracker only to look at my own data. No comparing to others, no trying to read between the lines, or understand the comments. It is such a useful tool for its literal purpose: tracking queries, finding agents. I will let myself glance at reports every now and then, but I won’t stare at them, I won’t check for updates daily or weekly, I won’t take them as a guiding light.

The only data I can trust on that website is my own, and even my own was incomplete. (For example: an agent I queried—an agent who requested my full manuscript—isn’t in the tool at all!)

I joked with my friends a few months back that you have to have boundaries with your dreams sometimes. For me, the key was not letting the double-edged sword cut me as much as possible, especially in a process where I was raw, anxious, yearning. Something is always better than nothing, but remember that it is something and not everything. Keep using QueryTracker! I’ll probably keep my paid subscription for a few years because I think that the tool is so helpful! But don’t let it govern your days. Don’t use tools that can help you against yourself.